From rebuilding to retrofitting, Tech-Way finds a way

Custom injection molder Tech-Way Industries Inc., Franklin, Ohio, is challenging the way the market looks at business in more ways than one. It is incubating three medical device manufacturing firms and touts itself as the only privately held medical incubator in the Buckeye state. Moreover, the company essentially builds or rebuilds its own equipment, depending on customer requirements and production needs. Its owner and president, Ken Parker, certainly doesn't think anything of acquiring an older press, tearing it apart and rebuilding it with new components, including customized programmable logic controllers.

The company routinely retrofits older equipment to make it competitive with newer machines. That alone allows Tech-Way to compete with Asian suppliers. Officials say they build machines exactly to their specifications and they are able to control everything as precisely on a retrofit as they could on a new machine. This is their economic reality: a savings of $135,000 when the company needed a two-stage rotary injection molding machine.

"It was one of these things where you can buy the equipment and spend $150,000 on it or you can take a look at your machines, think for 20 minutes and decide how to do it for $15,000. We took the cheap route," says Parker.

There is a bit of irony to this story, though. Parker and Tech-Way VP Brian Kress own and operate Tech Bole USA, through which Bole injection molding machines are sold.

Within its molding factory, located between Dayton and Cincinnati, Tech-Way houses 40 injection presses and has at least one press made by most major suppliers. So, officials are not just using the machines they sell. This factory is a playground for machinery geeks and engineers who love to tinker. Parker does just that each day.

"We keep components of the machines in case we ever decide to use them on something else," he says.

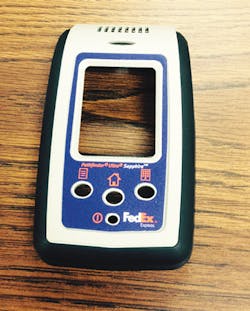

The company is plenty busy now, boasting the launch of more than 50 new tool builds this year. Its end markets include the medical, military and consumer industries. It also makes products for the scanning industry, such as the guns used by FedEx to scan barcodes for accurate delivery of packages. The components for such guns are molded in Tech-Way's plant via a two-stage rotary process where Santoprene is overmolded onto a PC-ABS substrate.

"There really is no biggest end market for us. We are very diversified," says Parker, adding that no single end market represents more than 25 percent of sales. "We have, over the years, stayed away from the automotive industry. That is by choice. I have done work with the automotive industry before but primarily on a consulting-type of basis where we were helping with a project that they couldn't figure out how to do. And then if we got production for a while, that was just gravy."

Building a press to meet its needs

Tech-Way had become involved with a production job that required a very small shot, but at the same time required several slides, including cylinders, and core-pull circuitry. Therefore, the mold had to be larger than desired for what was considered a micro injection machine. But the required shot size was quite small, says Parker, about 0.15 ounces.

"Most people, when they make micro molders, work on the idea of a micro-sized mold as well. We wanted more flexibility," he says.

Tech-Way designed a special injection system from scratch, then had it built by an outside supplier. This included a 12mm screw, complete with a non-return valve that was designed by Tech-Way. The company also designed and constructed the hydraulics and the frame. The screw has an electric variable-frequency drive for improved control, Parker says.

"With this system, we can run extremely small molds as well as molds which would go in larger machines," he says.

Here comes some history for machinery fanatics. When it came to the clamping mechanism, Parker and crew wanted a standard ejector system and they also wanted a standard clamping mechanism. They started with a 1969 Newbury 30-ton frame, then designed the platens, ejector system and tie bars. Upon completion, they had an 8-ton hydraulic clamp, rather than the original toggle clamp.

The control system also was built from scratch and this included program design, hydraulics (servo-valve designs) along with touch-screen operation, says Parker.

"As such, we have extremely good control over the system," he says. "Several people coordinated to build this and this has proven to be a fantastic machine for us. It has been such a good machine, we're presently constructing another with some improvements in the screw and barrel mechanism."

The machine will process PC, PEEK, polyetherimide, nylon, polytetrafluoroethylene and ABS. Parker says it likely is the most reliable machine he has ever seen, requiring only standard maintenance of oil, filter replacement, etc. Tech-Way runs the machine in its Class 100,000 clean room. The company pipes the tank air outside the room to keep the controlled atmosphere intact.

Parker is on the plant floor every day, side by side with employees, some of whom know his name and others of whom might not. He prefers it this way. The incubating companies have roughly 45 employees.

"For the most part, half of them don't know who I am yet," he says of those 45. "But that also goes for some of my employees, particularly the temporary employees that we have. They are usually very surprised to find out that the guy who is downstairs helping program or work on equipment is the guy who is also signing the payroll." For Parker, it doesn't matter if an employee knows who he is. Typically, if an employee knows, he or she will tend to get very formal.

Should an employee call him Mr. Parker, he will correct that very quickly.

"My name is Ken," he continues. "I don't need to be called 'mister.' We are all trying to get the same thing done here. So if I go downstairs and get my hands dirty, that is part of the game."

Kress says this attitude is what helps make the company so successful.

"He is the most hands-on owner I've ever seen and I've been in a lot of places," says Kress. "That is part of what really makes this place work as well as it does with as few people as we have. Everybody here is doing several different functions. They are not pigeonholed. People are pretty much busy all the time."

On this Tuesday in early June, Ken Parker is walking the floor with Kress and Susan Parker. He's analyzing the machines, particularly the control systems.

"All machines, if you take care of the molds properly, you've always got a good piece of iron," Ken Parker says. "So what we do is we take the old controls out, we'll put together a new control system, and then design and build the wiring and do everything here. We'll wire it up and program it to have it do what we want to do, which is the advantage of using the basically open-technology Allen-Bradley-type systems that we've run over the years. Allen-Bradley is not the only one. There are other manufacturers of programmable logic controllers. We just settled on Allen-Bradley because it was easier for us."

Rich heritage,

future-minded

Tech-Way and Ken Parker have a rich history. Ken Parker's father, Robin Parker, started Tech-Way in 1964 with partners Bill Gaiser of the former Broadway Mold and Tool based in Dayton, Ohio, and an attorney and an accountant. Robin Parker had been with General Electric in Louisville, Ky., where he honed his expertise in injection molding and materials. He still is alive; Gaiser passed away last year.

The partners started with a 28-ton Arburg Allrounder. Gaiser, as VP, brought work to the company for 15 years. Tech-Way grew from a one-machine shop to having 11 injection molding machines ranging from 30 to 400 tons of clamping force.

"We still have a few of those, although they have been heavily modified since then," says Ken Parker.

During the tour, a technician was working with golf balls molded from sodium ionomer. The golf ball has had its weight reduced by 60 percent over the traditional golf ball. The balls are molded on two machines — a 1986 HPM 110-ton unit with custom controls and a 100-ton Newbury, also with custom controls.

"This has no core, but yet this is a solid ball," Parker says. Since the ball has a foamed interior, it does not have a traditional golf ball core.

The pump that drives the HPM machine is a servo-internal gear pump, complete with its own driver system. This system spins only at the rate it needs, automatically adjusting the revolutions per minute of the motor according to the actual energy needed for each action. The drive runs the motor at the speed that is needed to complete the molding cycle. From the control system, the equipment is told how much pressure and control are needed, and then through its own closed loop system, ensures that it operates correctly.

"It just adapts itself to what we need," Kress says. "When we're done with this part of the cycle, it's just going to sit. It won't do anything."

This system is being sold by Tech-Bole as retrofits under the brand name Synmot. This is from Zhejiang Synmot Electrical Technology Co. Ltd., Ningbo, China, which is part of the same company that makes Bole machines. RSW Technologies LLC, Rossford, Ohio, just finished retrofitting a large machine for Tech-Way in which it used three of the pumps.

Elsewhere in the facility, officials are using rapid prototyping for parts via 3-D printing. More machines will be added in the near future. Kress explains that several years ago Tech-Way worked with the U.S. Army Marksmanship Unit, Fort Benning, Ga., to resolve an issue with the help of rapid prototyping.

Special forces were having problems with their guns' magazines jamming, especially in the Middle East where sand is abundant. Tech-Way designed and manufactured a product that would clear the sand and allow the gun to fire.

"We went through 27 revisions down there with the gentleman we were working with and we could change the data, make a part overnight, send it the next day," says Kress. "Our [prototype] material was strong enough they could actually load them in the magazines and test them out. But it was just having the rapid prototype ability, we could quickly see what worked, what didn't work, advance this thing and really help out with their engineering and development."

Supporting medical device startups

Tech-Way's business also is focused on getting other companies started, in this case, medical device manufacturing companies. Three companies share space within Tech-Way's 90,000-square-foot facility: Minimally Invasive Devices Inc. (MID), Columbus, Ohio; and Enable Injections LLC and NanoDetection Technology Inc. (NDT), both of Franklin.

MID's products include FloShield, a system to keep camera lenses clear during laparoscopic surgeries.

Enable develops and manufactures devices that allow patients to self-administer high-volume drugs or viscous biological drugs such as those needed for cancer treatments. Patients can use the discrete, wearable devices while performing normal daily activities, according to Enable's website. NDT is focused on pathogen-detection techniques.

For these companies, Tech-Way has developed a very large clean room and laboratory area within its facility. Tech-Way also has its 4,000-square-foot clean room in which it is molding these companies' products as needed.

MID now has entered production manufacturing that Tech-Way is handling.

"It has worked out very nicely," says Ken Parker. "What we have here, as opposed to most incubators, is that we have the prototyping capability in house, we have the engineering capability in house, and it's a friendly enough arrangement that I can walk into their areas, they can walk into ours and just ask the questions very quickly."

Angie DeRosa, managing editor

Contact:

Tech-Way Industries Inc., 937-746-1004, www.tech-wayindustries.com