University team designed, printed nasal swabs during pandemic

By Bruce Geiselman

As personnel in a 3-D printing lab at the University of South Florida in Tampa prepared to begin working from home due to the pandemic in early 2020, an urgent request soon had them working at the lab nearly around the clock, and seeing very little of their homes for most of the rest of the year.

When supply chain problems led to severe shortages of critical nasal swabs, Tampa General Hospital, which serves as a teaching hospital for USF Health, reached out to faculty researchers for help. The USF Health, Morsani College of Medicine, Department of Radiology’s Division of 3D Clinical Applications, which prints anatomical models and cutting guides for surgeons performing procedures like cardiac and craniofacial reconstruction surgeries, was asked to supply critically needed nasal swabs.

The 3-D printing lab, with help from colleagues specializing in infectious diseases and otolaryngology, developed a nasopharyngeal swab. The lab was then tasked with printing the swabs for use at Tampa General Hospital, Moffitt Cancer Center, the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital and the Bay Pines VA Healthcare System. They also ran a multisite national clinical trial, where they provided their files to collaborators across the world to help the international response to COVID-19.

The small lab, with two full-time employees assisted by occasional volunteers, over about a year managed to print 100,000 swabs for use locally. In addition, after developing files for printing the swabs, USF made those files available to hospitals and health care systems across the world. More than 70 million swabs using USF Health’s design were printed in 55 countries.

A call for help

In March 2020, the lab employees were preparing to transition as much work as possible to their homes when they received a request from Dr. Charles Lockwood, senior vice president for USF Health and dean of the USF Health Morsani College of Medicine.

“We swung through [the] infectious diseases [department], and they had one spare standard of care swab that they were willing to part with as a reference,” Dr. Jonathan Ford, a biomedical engineer and technical director of the USF Health 3-D lab, said.

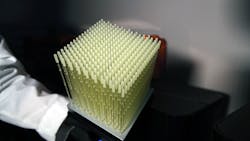

The standard swabs have a polyester flocked head — an absorbent material for collecting specimens similar to a cotton swab. However, USF Health researchers knew they couldn’t produce that same flocked head, so they had to devise a different solution. They were able to replicate the standard swab’s sample collection capabilities by creating rows of “nubs” that allowed for sufficient collection of mucus and tissue needed for the COVID test.

“We knew we couldn’t print absorbent material, so it had to act kind of like a scraper,” Ford said. “We designed several heads — I think a total of 20 to 30 heads, and we printed them out and took them to our infectious disease colleagues. They all tried them on themselves to see which one they liked best. Then we also handed them to our virologist, who was able to do the bench lab testing to make sure they could grab enough of a sample and to make sure they wouldn’t interfere with any PCR [polymerase chain reaction] testing.”

Luckily, the tests proved the 3-D printed nasal swabs were effective and the material used did not interfere with the accuracy of the COVID-19 test results. Clinical testing on patients for safety and comfort showed that the 3-D printed swabs performed as well as the standard swabs.

Sharing the design globally

Due to the extreme supply chain shortage and the impact it was having on COVID response in New York City, USF Health shared the information with its counterparts at Northwell Health, New York’s largest health care provider, which also began printing nasal swabs and testing them.

That meant that within only a few weeks, USF researchers developed the plans for 3-D printed COVID testing swabs and began production.

In addition, USF Health knew that Formlabs printers are commonly used in health care systems around the world. USF Health reached out to Formlabs to ensure they had an adequate supply of resin for printing large numbers of swabs.

Once production of swabs ramped up in the USF Health 3-D lab, employees were working nearly around the clock and slept in the lab, Ford said.

“That was painful,” Ford said. “For the first 200 days that we worked, we would only come home to shower. We didn’t have a weekend. For 200 days straight, we worked through. We ended up locally making about 100,000 [swabs] just for our medical system … We were trying to develop the best methods of post processing because you print them; then you have to wash them in isopropyl alcohol; then you have to UV cure them; then you have to autoclave them. We were working out that process and were working out the distribution process.”

Burning the candle at both ends

While devoting as much time as possible to producing nasal swabs, Ford and colleague Dr. Summer Decker, director of the 3D Clinical Applications Division in the USF Health Morsani College of Medicine, still had their regular job responsibilities printing models and tools for surgeons.

“We also had our day job, which didn’t stop,” Ford said. “All of a sudden, between May and July, we just got slammed with our clinical caseload for facial traumas. People were either driving too fast and getting facial traumas or they were getting in fights.”

Ford also had to deliver lectures to medical students on imaging anatomy during the same time.

Normally, medical school students would assist Ford and Decker in the 3-D lab, but the students weren’t allowed into the building because of COVID, Ford said. On occasion, surgeons, who were unable to perform their elective procedures during the pandemic, would volunteer to assist with 3-D printing tasks.

Their workload only recently let up as adequate supplies of commercially produced nasal swabs once again became available, which eliminated the need for USF to print their own.

“As of this month, I have stopped, thank goodness,” Ford said during an early May interview. “I have a huge stockpile, and they have a decent shelf life if you keep them out of the light.”

Ford said that developing and producing the swabs was a team effort and he is grateful for everyone that contributed and provided assistance.

Bruce Geiselman, senior staff reporter

Contact:

University of South Florida Health, Department of Radiology, Division of 3D Clinical Applications, Tampa, Fla., email: [email protected], https://health.usf.edu/medicine/radiology/3d/about3d

More on medical parts and plastics

Parts makers step up their processes to meet needs

Health-care market keeps IMM makers busy

Injection unit, machine dedicated for test tubes among new processing technologies

Extruder OEMs respond to changing medical landscape

Auxiliary makers prioritized medical orders during pandemic

Robots shine in clean room duties

Economist: Run on medical goods provided jolt to plastics manufacturers

Geisinger’s 3-D lab printed devices to help health care workers stay safe

Beckwood Press designs compression molding equipment for medical devices

Quick deliveries, new products: Husky details COVID-19 response

About the Author

Bruce Geiselman

Senior Staff Reporter Bruce Geiselman covers extrusion, blow molding, additive manufacturing, automation and end markets including automotive and packaging. He also writes features, including In Other Words and Problem Solved, for Plastics Machinery & Manufacturing, Plastics Recycling and The Journal of Blow Molding. He has extensive experience in daily and magazine journalism.