By Bruce Geiselman

Pretium Packaging, a designer and manufacturer of rigid packaging, including PET and HDPE blow-molded containers, was contemplating buying new equipment to boost productivity. Then, it invested in a monitoring innovation from smart factory software maker Guidewheel — and the plug-and-play system has allowed it to achieve efficiencies without new machinery.

“We started at a low 60 percent utilization, and now we’re at mid-70s, and I can only see that improving with the real-time information that we’re getting day in and day out,” said Cynthia Melendez, a Pretium plant manager, in a case study published on the Guidewheel website.

The company’s FactoryOps software so far leverages information from electric current sensors because of the amount of data they can provide. However, the technology also is designed to work with other sensors, such as sound, vibration, temperature and pressure, Dunford said.

Supply chain kinks and a labor shortage are forcing manufacturers to be more efficient than ever, but most manufacturers are intimidated by the cost and complexity of adopting smart factory technologies, she said.

“A lot of folks are still managing manually or have sets of clipboards or spreadsheets across the plant and especially across multiple plants,” Dunford said. “What we see as really challenging for folks is that historically, the only options to get smart factory [technology] have been very heavyweight, very inaccessible from a time, effort, cost and usability perspective. Where we come in as Guidewheel is with a new category of software that is not heavyweight and all-or-nothing.”

Guidewheel allows manufacturers to progress at their own pace toward maximizing efficiency through process monitoring, artificial intelligence and predictive maintenance, whether they want to crawl, walk, run or fly, she said. The most basic level of smart factory technology involves gaining real-time transparency into how equipment is performing. The system can evolve to the point where it’s fully connected and teams use data in the cloud to predict and head off problems, react more quickly to issues and prioritize their time to boost efficiency.

Guidewheel recommends its clients start by monitoring the most important equipment in their manufacturing process, such as primary plastics processing equipment, and eventually expand the monitoring to include auxiliary equipment such as chillers, compressors and pumps.

“We can get all that equipment consistently into the exact same system in real time,” Dunford said. “We have built the platform to take in a variety of different sensor types; we always start with [electric] current.”

Guidewheel’s cloud-based software collects real-time data from machines in the factory through non-invasive sensors called current transformers that clip around the power cord of a machine like a bracelet without the need for any integration. They track the activity of the machine by tracking the current it is drawing. They work the same way for any machine that uses electricity regardless of its make, model or age, according to the company.

“The electrical heartbeat is so great for identifying with precision exactly where you’re losing that potential runtime — that lost production time that is lost potential revenue,” Dunford said.

Using that information, the software can identify the most productive pieces of equipment and operators, which can create additional training opportunities. In addition, changes in the amount of current a machine is drawing can signal maintenance issues that need to be addressed.

It is common for Guidewheel customers to quickly experience a 10 percent improvement in run time after they begin collecting real-time data, and that can increase to a 20 percent improvement over time, Dunford said. As workers become aware of trends, they become more proactive about identifying potential malfunctions or problems before they arise.

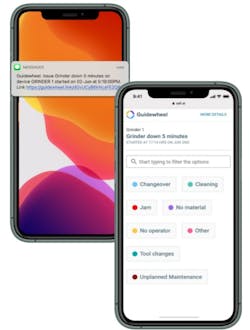

In March, Guidewheel announced it was introducing what it calls “escalating alerts.” When machine downtime occurs, the FactoryOps software sends alerts to front-line workers. The feature provides data-driven analysis of issues that need to be resolved to specified people. If a problem is not corrected within a specified time, the alert is escalated to other individuals, such as operations leaders, so they can intervene.

The software also can identify which machines can accept jobs so companies can maximize overall equipment efficiency.

“You’ve typically got some big room to improve in terms of setup time, changeover time and how these machines are being run,” Dunford said. “We have the ability to identify where operators are doing a phenomenal job and pair and cross-train with areas that might benefit from some improvement, especially in today’s environment where labor is a bit of a challenge.”

Information from the FactoryOps software can be communicated to customers through smartphones, laptops and tablets.

Guidewheel’s plug-and-play approach to collecting data reduces the costs and complexities of adopting smart factory technologies, but it has limitations.

“The No. 1 limitation is we are not controlling the machines,” Dunford said. “This is not a system where someone is going to be able to tap a keyboard and change what the machine is doing. Our sensors are completely non-intrusive. They are clipped around [the power cord of the machine]. They’re measuring only and not controlling. If someone wants a system that’s going to automatically drive the machines or change what they’re doing, Guidewheel, at this moment, we don’t have that functionality yet. We may in the future, but not yet.”

Identifying extruders in need of screw repair or cleaning is one example of how Guidewheel’s FactoryOps platform can assist plastics processors.

“I also heard an example from one of our customers where they were getting a lot of burn lines in their final product — seeing it all over the place but unable to pinpoint exactly what was happening,” Dunford said.

However, when the company used Guidewheel, it pinpointed that all the burn lines were tied to a particular extruder that needed maintenance, she said.

In another example, a processor noticed that an extruder’s runtime was much higher than expected. Further investigation revealed that a lack of production stoppages stemmed from the extruder not being properly cleaned on a timely basis. Identifying the problem allowed the processor to intervene and clean the extruder before a serious problem developed with product quality, she said.

Based in St. Louis, Pretium initially adopted FactoryOps as a pilot project in a couple of plants in an effort to implement a standardized way of sharing process improvements across regions to achieve peak performance. In less than three months, it experienced a 15 percent improvement in equipment utilization in less than three months, according to the case study. Within a year, the company was using Guidewheel’s technologies in 19 of its plants worldwide, and the number of plants has since grown to at least 25 with additional acquisitions.

Bruce Geiselman, senior staff reporter

Contact:

Guidewheel, San Francisco, 925-683-7646, [email protected], www.guidewheel.com

Bruce Geiselman

Senior Staff Reporter Bruce Geiselman covers extrusion, blow molding, additive manufacturing, automation and end markets including automotive and packaging. He also writes features, including In Other Words and Problem Solved, for Plastics Machinery & Manufacturing, Plastics Recycling and The Journal of Blow Molding. He has extensive experience in daily and magazine journalism.