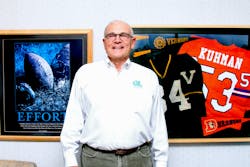

In Other Words: Jeff Kuhman, from pigskin to plastics

Jeff Kuhman has had two careers in his lifetime. He had a brief stint in professional football and then parlayed what had been an off-season job in the plastics machinery industry into a full-time career spanning more than 50 years.

Kuhman was a record-setting tight end on the University of Vermont’s football team. His play generated enough interest among pro scouts that he was drafted by the Denver Broncos. He ended up in Seattle playing in the now-defunct Continental Football League. The highlight of Kuhman’s pro career came in Seattle, where he intercepted a pass from future NFL Hall of Famer Ken “The Snake” Stabler and returned it for a touchdown.

During the off season, Kuhman worked at the Hartig division of Midland-Ross Corp., which manufactured extruders and blow molding machines. When he retired from football, he joined Hartig, setting him on the path to founding the company that would become Glycon Corp., a maker of feed screws and a variety of aftermarket parts for extrusion, injection molding and blow molding machinery.

Highlights from Glycon’s history include the development in 1998 of a high-output screw for the blow molding industry, the creation of its QSO (quick shut off) non-return valve for injection molding and the ongoing development of its electronic measurement and tracking system for predictive maintenance.

Kuhman discussed his career, company and sports with Plastics Machinery & Manufacturing Senior Staff Reporter Bruce Geiselman.

When was Glycon established and how many employees do you have?

Kuhman: Glycon was established in 1978 as Great Lakes Feedscrews, and in 1997 it became Glycon Corp. Currently, Glycon has 32 employees on one shift. We discontinued our second shift during the pandemic as a precautionary measure. To date, we have been very fortunate in our shop. Our personnel reductions have been primarily through attrition, and to date we have not lost anyone to COVID.

How has your business been affected by the pandemic?

Kuhman: Our 2020 sales were off by about 12 percent. However, we remained profitable. Our people feel fortunate, and they deserve the credit for being diligent.

Where did you go to college?

Kuhman: I graduated from the University of Vermont in 1968 with a major in economics. I chose the University of Vermont because of its location in a beautiful part of the country and for the opportunity to combine the academics and athletics.

How did you go from studying economics to playing professional football?

Kuhman: I was very fortunate to play on some excellent teams and to get noticed by professional scouts and was drafted by the Denver Broncos. My career was short, though. I was on Denver’s roster for two years. The first year, when I was in Denver, I was on the practice squad, and I was optioned out to Seattle in the Continental Football League. For all practical purposes, it was Denver’s farm team, but it was a wonderful experience.

I was just married after I graduated from school. My wife and I moved from Denver to Seattle, and we had a great year out there as far as football. I was a tight end in college, and I was drafted as a linebacker, so it was a new position. I started every game in Seattle until I was recalled by Denver in November.

How did you end up in plastics?

Kuhman: At the end of my second pro season, I had two off-season job offers. One was from Monsanto and the other was from Hartig, a division of Midland-Ross Corp. Harry Bolwell, one of my mentors, was the CEO at Midland-Ross. I chose Hartig. Hartig manufactured extruders and blow molding machines. Welcome to plastics!

We moved to New Jersey in 1969, and I began my career in plastics during the off season. I really enjoyed what I was doing, so I decided not to return to camp and to pursue a career in plastics.

What did you do at Hartig? Did you have any other jobs prior to forming Glycon?

Kuhman: I started in the lab and was eventually promoted to the product manager, blow molding. While I was at Hartig, I had the good fortune to work with some outstanding people. In the early ’70s a group of us left Hartig to form Barr Polymer Systems Inc. Our target was the rapidly developing market for large blow molding machines.

The Barr team worked closely with Phillips Petroleum Co. and talented people like Don Peters at Phillips. Barr built machines for 55-gallon drums, automotive fuel tanks, cooler chests and other large parts.

However, our timing was not good and, during the recession of 1973 to 1975, we were forced to sell to Uniloy, in Michigan. Uniloy was looking to complement their smaller reciprocating screw line with the larger industrial machines. We had a full order book, and they had capital, so it was a good deal for both parties.

I joined the Uniloy team in Michigan as manufacturing manager.

Why did you leave Uniloy to form what is now Glycon?

Kuhman: I had worked with extrusion and blow molding machinery for 10 years up to that point and I was blessed to have been associated with some of the leaders in the industry. Names like Dr. Chan Chung, John Hsu, Robert Barr, Mark Spalding, Jim Frankland, Paul Colby, and the aforementioned Don Peters. Many of these people were the real pioneers in the feed-screw technology field.

At Uniloy, my responsibilities included purchasing screws and barrels. When Mr. Barr left Uniloy to start Barr Inc. and John Hsu left to join Hayssen and my former Hartig associate Peter Schmidt joined Kautex, they each needed a source for screws and barrels, so I became their guy. I left Uniloy and formed Great Lakes Feedscrews in 1978.

What makes your company stand out?

Kuhman: We work directly with plastic processors to solve problems … to improve performance and longevity. With over 40 years in business, we have accumulated an impressive library of drawings of screws and barrels. If we don’t have the drawing, we will travel to the customer’s plant, measure the screw and generate a drawing.

Additionally, Glycon’s technicians are experienced on performing laser alignments, bore scoping, checking feed housings for wear and solving processing problems. They work directly with the customer to improve performance. When we measure for wear, we look for solutions to extend the life of their screws and barrels.

What made you think you could succeed in such a competitive field?

Kuhman: It was certainly a challenge, but as I said earlier, there were some excellent opportunities. One of the best breaks was the chance to supply Uniloy, the company I left. They became our leading customer for quite a few years.

As I traveled in the Michigan, Ohio, and Indiana region, I quickly discovered the great opportunity for screws, barrels and non-return valves for injection molding. Ford Motor Co.’s Saline Plant with 312 injection presses was 16 miles from our plant. Our product mix changed dramatically, and we were not only a supplier of blow molding and extrusion aftermarket parts, but injection molding rapidly became a major part of Glycon’s business.

Is that why you changed the name from Great Lakes Feedscrews to Glycon?

Kuhman: Not so much. At the time, we thought “feed screws” did not adequately describe our product line. We sold barrels, feedthroats, nozzles, non-return valves and tie bars, as well.

Where did the name come from?

Kuhman: Too many people said don’t give up that “GL” logo. Mr. Barr’s wife said, “That logo is an icon.” So, we combined the two and came up with Glycon.

How have feed screw designs changed over the past 43 years?

Kuhman: They have progressed significantly. Feed screws are asked to perform much more difficult tasks. The designs are based much more on the properties of the materials to be processed. They are no longer empirical designs like metering screws, mixing screws or general-purpose screws. Today, they have to perform more complex tasks that include alloys of polymers, additives, colorants, recycled, bio-based and biodegradable. These are all things that didn’t exist 43 years ago.

You’re saying screw designs are more specialized today?

Kuhman: Exactly. Today you find much more specialization because there is a big difference in productivity and the integrity of the part you are producing. There are situations where if you don’t change screws, scrap rates can increase dramatically, and processors can’t afford that. They have to match the screw to the application.

Have you seen significant growth in any particular segment of the industry?

Kuhman: No question about it. When we started the business, over 50 percent of our business originated in the automotive markets. Today, if you combine packaging, recreation and leisure, agriculture and construction, those areas make up 75 percent of our business. Those markets have grown more than the automotive. I think the largest market for Glycon today is probably packaging.

Who was your mentor in the early years?

Kuhman: Probably Harry Bolwell. He was the CEO of Midland-Ross Corp., but he was also a University of Vermont graduate and a football player. Mr. Bolwell recruited me for Vermont and then Midland-Ross.

What’s the greatest business lesson you have learned?

Kuhman: To listen. To be a good listener and to respect and learn from others … including my employees, my customers and my competitors.

Just the Facts

Who is he? Jeff Kuhman, chairman and CEO of Glycon Corp., and recipient of the SPE’s Ironman Award in 1999

Headquarters: Tecumseh, Mich.

Company founded: 1978

Employees: 32

Age: 75

Patents (sole or co-holder): Six