'Old clunker' press weaves its way through history

I am always pleasantly surprised when I go into a machinery maker's lobby and see its first machine proudly displayed. The technology may be ancient, but the ingenuity and craftsmanship are evident.

My first thought is always, "How did that first guy figure everything out?" My second thought often is how similar the original design and functionality are to today's modern version. That's a sign that the inventor got it right.

The best early machine displays come with a good story, such as the one behind the first injection molding machine Milacron ever sold.

In 1967, Cincinnati Milling Machine Co., which in 1970 became Cincinnati Milacron and later Milacron LLC, was a machine tool company before it got into the plastics machinery business. The initial thought was to make extrusion equipment, but a small group of engineers was assigned to work on an injection molding machine. They built three prototype presses and took one to the NPE show in Chicago in June 1968.

Officials from Mid-Central Plastics Inc. in West Des Moines, Iowa, saw the machine running at the show and recognized it as an improvement over the New Britain, Newbury and Reed machines they were running.

The Goreham family, which owned Mid-Central Plastics, tried to purchase the machine at the show but were told it was a prototype and not for sale. Undaunted, the owners asked for a Cincinnati Milling salesman to visit, and after the show Cincinnati Milling sent Tony Lutarewych, who eventually convinced his bosses to sell one of the three 1967 prototypes to Mid-Central.

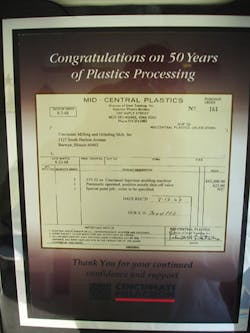

The deal, as shown on the Mid-Central purchase order dated Aug. 7, 1968, was for a 375-ton Cincinnati Milling press with a 32-ounce shot at a cost of $43,825. Mid-Central's only request was that the press be painted the same color as the Cincinnati Milling machinery it already owned. Standard equipment listed on the invoice included a position nozzle shut-off valve and an ejector bar, which was a new safety feature at the time.

That was the first injection molding machine sold by Cincinnati Milling.

Mid-Central, founded in 1960, was sold to Bob Janeczko in 2003. He changed the company name to Innovative Injection Technologies Inc., known as i2-Tech. He is now chairman.

"That machine was still running on the floor when I bought the company," Janeczko said in a recent interview. It was used for a variety of products over the years, but Janeczko dedicated it to making a John Deere seed disc, the device that drops and spaces seeds as they come out of the spreader.

In 2010, Janeczko's son, Josh, said they "needed to get rid of this old clunker." But the elder Janeczko delayed. "I wanted our customers to see how we took care of our things," he said of the then 42-year-old machine.

"I called Milacron and told them we needed a new screw and controller for the 1967 machine, and they sent them," Janeczko said. "It blew my socks off that they had those parts."

After the upgrade, i2-Tech ran the machine until 2014. "By then, it had seen its better days," Jancezko said. "It had been our workhorse for many years."

But the 1967 model was not ready for the junk pile yet. Milacron took the old 375-tonner in on a trade for a new 350-tonner.

Janeczko suggested that the early machine could have another life as a showcase for a new business Milacron was just starting — refurbishing used machines. That's how it was rebuilt and now resides, fully functional, at the Milacron factory in Batavia, Ohio.

Cincinnati Milling did not have a logo for its fledging injection molding machine business when that first machine left the factory, so it screwed on a metal emblem used on its machine tools. Someone at i2-Tech found the original 1967 emblem in a tool drawer and gave it to Milacron.

Janeczko's company, which he sold to son Josh in 2014, runs 30 Milacron machines. So what did he notice most about the 350-ton press that replaced the first Cincinnati Milacron?

"The footprint is much less, probably 50 percent less," he said.

Robert Strickley, Milacron's VP of U.S. sales, East region, said those first three machines were built using the same technology Cincinnati Milling used in its precision machine tools. "This was new technology for injection molding machines at the time," he said. "It included advanced hydraulics and new motor technology. The three prototypes did not have the manual pressure valves that were common in those days."

Strickley acknowledged that the injection molding press has a huge footprint by today's standard.

What happened to the other two prototypes? Both were eventually sold by Lutarewych, but Milacron does not know what became of them.

Do you have an interesting story about an old machine? Send me information and it might find its way into Plastics Machinery Magazine.

Ron Shinn, editor

About the Author

Ron Shinn

Editor

Editor Ron Shinn is a co-founder of Plastics Machinery & Manufacturing and has been covering the plastics industry for more than 35 years. He leads the editorial team, directs coverage and sets the editorial calendar. He also writes features, including the Talking Points column and On the Factory Floor, and covers recycling and sustainability for PMM and Plastics Recycling.